There’s a chasm between the future and present that only humans cross.

Animals know nothing of the future beyond their whiskers; they confront the new from past conditioning, not imagination.

But humans discovered the future. In a god-like way, we conjure visions of things unseen and strive to bring them into being.

We transform wild frontier into thriving cities, fictional flying machines into self-landing rockets, and warring tribes into nations.

“We adore chaos because we love to produce order.”– M.C. Escher

The bridge between chaos & order is creative work.

Most of us have been taught to think of creative work as synonymous with art. But that’s a narrow definition, so let’s start by defining our terms:

Replicating something from a known pattern isn’t creative in this sense – that’s work.

Imagining something that doesn’t exist is creative but not work as long as it remains in our imagination or notebook.

Creative work is the process of making a newly imagined way of doing things work in reality – inventions of all kinds, shapes, and colors.

In this sense, a popular Instagram creator who skillfully paints in the popular style may be doing less creative work than the lawyer who finds novel loopholes within strict legal codes to win cases.

Faith is the prerequisite to creative work.

And I mean faith in the broadest sense of the word: we have to believe in the invisible future to risk present money, time, and often – reputation – to bring it into being.**

It doesn’t take faith to:

- stick with the safest career path,

- hold social positions aligned with our in-group’s mainstream or tradition, or to

- always follow a playbook or study guide.

But it also doesn’t take faith to be a dreamer who endlessly chases the grass that’s greener yet never quite finishes anything. True faith works.

Faith enables us to leave safety, step into chaos, and persist in the painful journey across the middle to bring back something valuable.

It’s easy to spot chaos – who can look away from it! And order is what we’re all immersed in now. But the bridge between the two – the epicenter of progress – is surprisingly unarticulated.

The first part of creative work is like dragging a dragon up a hill by its tail.

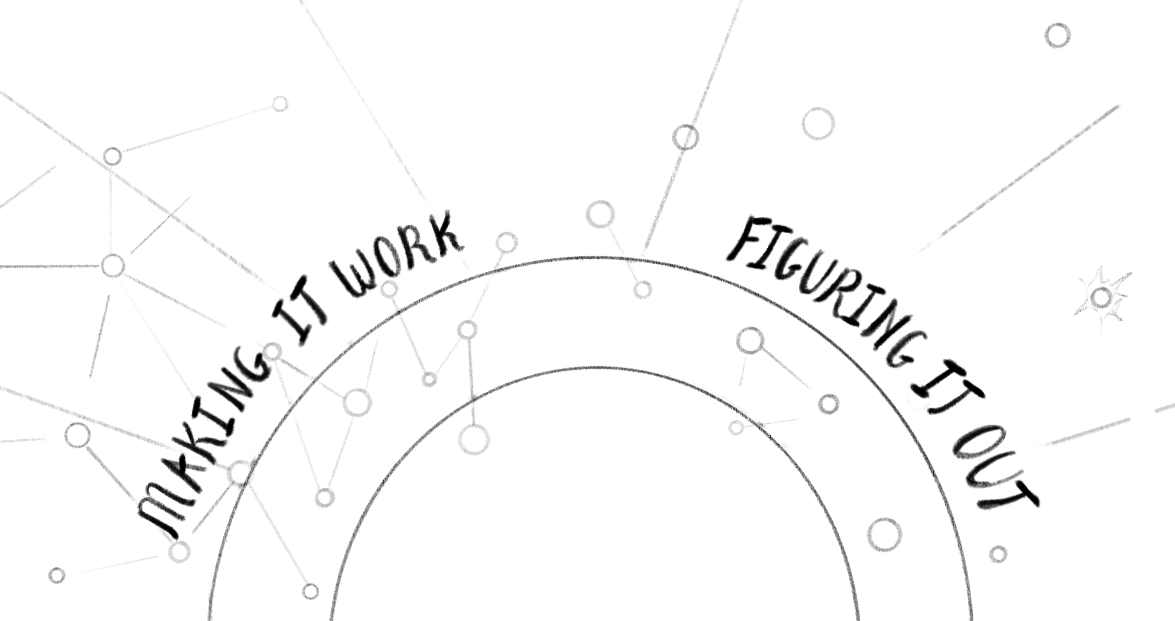

One of my favorite visual metaphors is the Hill Chart; It’s a simple, natural view of work created by Ryan Singer. I’ll reinterpret the Hill Chart in this essay as a metaphor for two halves of the bridge between chaos and order.

Uphill represents the “figuring it out” phase; Downhill represents “making it work.” We’ll focus on the uphill slope in this essay.

The uphill climb is where we tame a cacophony of speculative possibility into a timely, workable solution. It’s where divergent views in our minds and others’ minds battle it out among an endless number of what-ifs and what-abouts.

Uphill creative work moves an ideal partnership to a first meeting; A hopeless situation into a plan that just might work; A moonshot dream into clear next steps.

It’s rewarding, but in the middle of the climb, we – and others – may question our sanity or ability. The bigger the idea, the higher its toll. And like a real-life climb, the crest of the hill is never as close as it seems.

We can’t help but accumulate a few bruises and burns while fighting uphill with a chaotic dragon. But we can avoid a few common blunders and better our chances:

Blunders to avoid when moving creative work uphill:

The Rushed Opening is when we impatiently push new ideas over the hill to the make-it-work phase too quickly. Instead of taking the time to grapple with the messy ambiguity of it, we put on blinders and make decisive, quick cuts to keep momentum. Rushing is an effective executive move. But quick cuts lop off-key insights and subtle risks alike. The half-formed solution tumbles down the other side too ill-formed, untamed, or ill-timed. If it survives the downhill slope, then at best, it doesn’t make the good impact it might have given more care on the way up; At worst, it destroys more than it helps.

Creative work can’t be rushed without someone paying the price later.

The Neverland Adventure is the opposite of the Rushed Opening: instead of moving too quickly, we remain too long intoxicated by the chaotic potential of our idea. We jump from connection to connection exploring all the potential lest we miss something.

There’s a legitimate cost to taking a pattern we’ve found in chaos to reality: at worst, the uphill climb will kill the vaguely beautiful theory we’ve enjoyed exploring so much; At best, our dream will undoubtedly diminish as it becomes more realistic. Nothing survives the climb fully intact.

It’s easier to forgo the risk and pain. But if our dreams never manifest in reality, then our creative faith without the work remains lifeless.

The Sisyphus Trap is one many creative workers fall into. Like Sisyphus, we endlessly carry the creative burdens of someone else up the hill, again and again, never accumulating the reward.

We learn the perils of creative work early, so there’s an appeal to housing it within the safety of someone else’s budget, reputation, and abilities. That’s well and good. We all work within the order formed from the creative risks of generations before us. But there’s a snake in the garden: many powerful people have mastered the art of exploiting creative workers.

Exploitative clients, bosses, investors, and politicians dose out zealous visions, frantic expectations, and just enough money to push more creatively willing people into the unknown on their behalf. But chaos doesn’t fully answer when we’re asking only to keep the safety of someone else’s approval or paycheck. The uphill creative effort is constantly rushed, so the results are meager.

But these power-hungry tyrants won’t be satiated; After all, they’re accruing the rewards of creative work for only a token of risk (money). They’ll roll those dice again and again, and who wouldn’t with that risk-to-reward ratio?

So the creative workers starve while their agents, record labels, and investors grow rich.

(This idea is for a future essay, but I believe that good leadership happens from the right side of a map. It leads the charge up the hill, bearing the most weight. It has creative skin in the game, not just a little monetary risk. Power exercised from within the safe, established confines of order isn’t leadership — that’s tyranny.).

How to know when you’ve crested the hill.

Chaos is vague and unwieldy by definition, so there’s no playbook or timeline for getting any particular idea up the hill. We can only avoid blunders and press on.

Here’s a good rule of thumb for determining if you’ve crested the hill:

- Poorly-shaped solutions grow more complex – opening more questions – the more time we spend with them. That’s the surest indicator that there’s still more hill to climb.

- Well-shaped solutions not only resolve the tensions and paradoxes we’ve been wrestling with but begin to solve more issues than we set out to solve. This expansive clarity is the summit.

At Pathwright, where I lead product design, we’ve learned to recognize when an architecture-level design is on the right track by noticing when it begins to unlock answers to longstanding questions we didn’t intend to solve.

When we reach this hilltop equilibrium between chaos and order, then we’re ready to embark on the downhill journey of making it work.

The second half of creative work is like sliding downhill with a dragon in tow without obliterating the order on the other side. In the next essay, we’ll explore the downhill side of the bridge between chaos and order.